From Long-range to 51% problems

A blockchain is defined as a chain of blocks, where each block contains a set of transactions. Based on this definition, an attacker, or a group of attackers, could select any block as a base point and attempt to create an alternate fork.

In this article, we’ll explore these potential malicious behaviors.

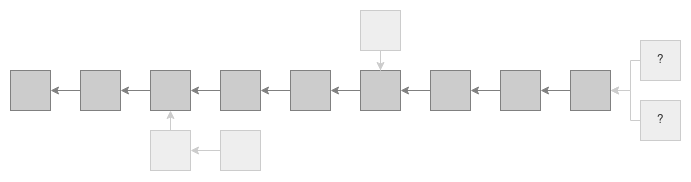

Long Range problem

In a Long-Range problem, adversary choose a block from the past and try to create an alternate chain starting from that block. The main goal is to rewrite the blockchain’s history By doing so, they can add or remove transactions they desire. Because the fork begins from an earlier point in the blockchain, it is termed as “Long-Range” problem.

Proof-of-Work

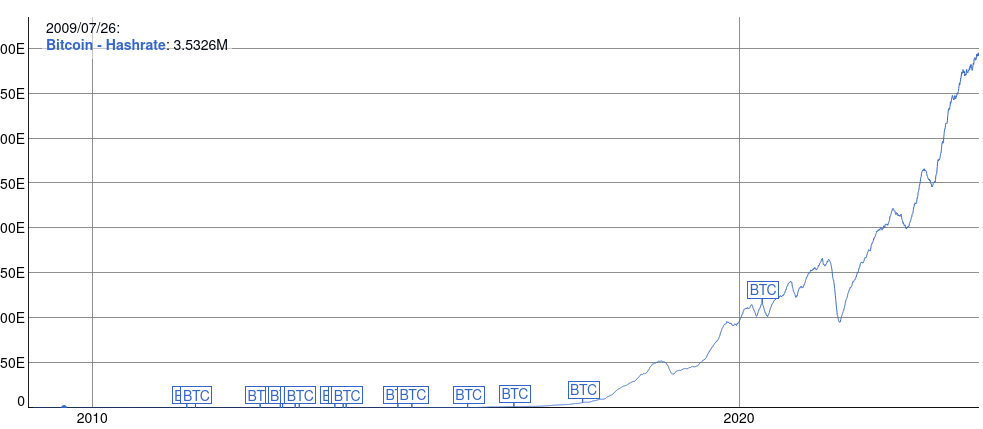

In the case of Bitcoin, since the hashing power has constantly increased over time, rewriting past blocks requires a huge amount of energy. It is almost impossible for the adversary to rewrite the last 6 blocks.

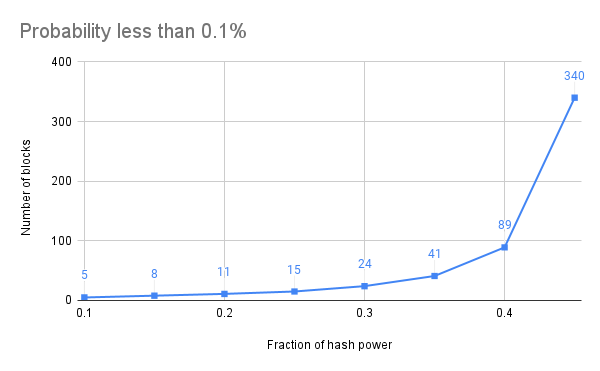

Indeed, Satoshi Nakamoto showed that with a probability less than 0.1%, an adversary with 10% of the mining power can rewrite the last 5 blocks (less than one hour), while an adversary with 45% of the mining power can rewrite the last 340 blocks (about 56 hours, or 2.5 days).

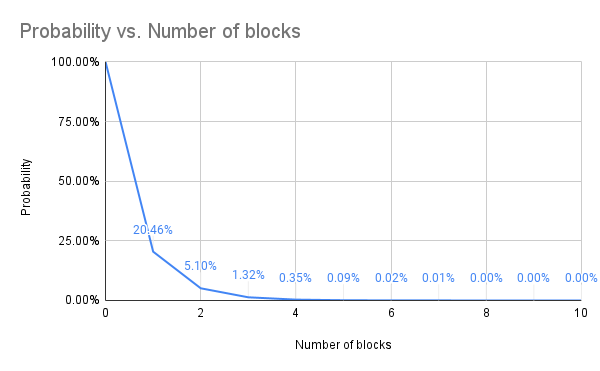

The chart below shows the probability of rewriting blocks by an adversary with 10% of the mining power.

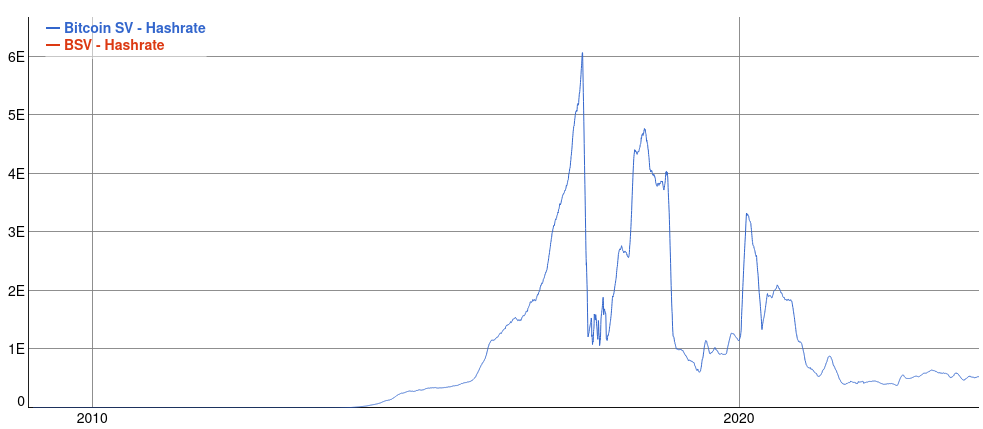

Unfortunately, many proof-of-work blockchains don’t have a hash rate growth like Bitcoin’s. In some blockchains, like Bitcoin SV, the hashing power even dropped over time.

Proof-of-Stake

This problem in Proof-of-Stake (PoS) blockchains appears more serious. In these blockchains, adversary can obtain (or even purchase) the private keys from early validators. If they possess enough keys, they can reorganize a new fork from early blocks (even from the genesis block!). Considering there is no actual work involved, just staking, reorganizing the blockchain becomes very easy.

Solution

So, as you can see, most blockchains appear vulnerable to long-range problem. However, this problem is not serious and can even be ignored. Simply because any chain that looks new can be ignored, and miners or validators can always add blocks to the chain they know.

51% and Nothing-at-stake problems

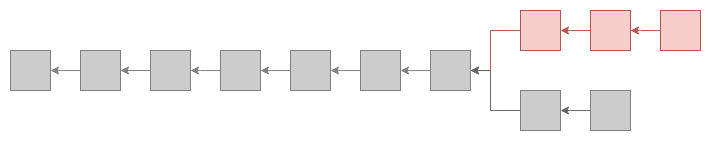

Attackers may choose to create a fork at the tip of the blockchain. By doing so, they can execute a double-spending transaction. For example, in one fork, Eve sends coins to Alice, and in another fork, she sends the same coins to Bob. This problem is known as the “51%” in proof-of-work blockchains and “Nothing at stake” in proof-of-stake blockchains.

Proof-of-Work

The consensus mechanism in Proof-of-Work blockchains doesn’t provide safety1. This means the blockchain doesn’t necessarily provide safety, and there might be more than one valid block at each height.

In the case of Bitcoin, forks can happen but very rarely. And since the hashing power is high, the chance of an adversary creating a fork longer than two blocks is really low. This is why in many exchanges, you have to wait for at least 2 block confirmations before withdrawing or depositing your Bitcoins.

Most people think that proof-of-work blockchains are more secure than other consensus types, but in the real world, Proof-of-Work blockchains are more vulnerable to this problem. For example, in Ethereum Classic, we have a history of a 51% problem by injecting more than 3000 blocks by only one miner.

Proof-of-Stake

If the consensus mechanism in proof-of-stake blockchains doesn’t provide safety, it is vulnerable to Nothing-at-stake problem.

In blockchains like Ethereum adversaries with enough stake can create a valid fork. To overcome these scenarios, there is a mechanism in Ethereum to punish the validators that double-vote in different forks.

However, other blockchains prioritize safety. In these cases, there’s no way to have a fork at the tip of the blockchain.

If a fork happens, it is the result of a bad implementation or, even worse, the majority of the nodes (with more than ⅔ of the total stake) are not loyal and honest. So, the Nothing-at-stake problem in these blockchains is not possible. Blockchains like Algorand and Pactus are not vulnerable to the Nothing-at-Stake problem, and therefore there is no need for a slashing mechanism there.